Every few months or so, we get a message from a customer that sounds like this:

I am looking to integrate JWT to my app. I found this tutorial and trying to follow it in my code. I am now trying to encrypt the signature with an RSA public key and decrypt it later with my private key to compare the hashes, but for some reasons my encryption results are always different.

If you don’t follow what’s happening, and I think most of my readers don’t, here’s what.

First, one guy publishes a tutorial that explains the townsfolk a general process of building a space rocket. Just take some titanium for the body, solder a guidance system (shouldn’t be that much harder than soldering that SatNav chip to your Arduino board), get some rocket fuel – just be careful, it is a bit super-deadly – and in a few months top you’ll be able to check for yourself whether the Great Wall can really be seen from space.

This makes Mick, an honest town lad, interested (he was a bit into rockets himself back in Y7), and he decides to launch a space travel business, using that tutorial as a guide for building his own space rocket. Mick decides to replace titanium with aluminum (as that is cheaper that way), but his aluminum doesn’t stay in shape as per the instructions because the feathering is too heavy for it. He feels frustrated and decides to get rid of some of the feathering.

Meanwhile, the town is getting interested in the project, and Mick’s bookings are growing steadily.

* * *

When my friend got her first car, her mum said to her: I’m super happy for you, darling. Could you please promise me that you will always bear in mind one important thing: it may not always look like that, but you are about to take care of a 3-tonne killing machine. Please be careful.

My friend recalls these words every time she turns the key.

We need to grow up. We need to understand that security is serious. We need to bear in mind that by integrating security into a product we are taking care, well, not of a killing machine, but of something of a very similar scale. Taking it lightly is extremely dangerous.

And I think Mick is as much of a victim here as his customers are. Tutorials like the one mentioned in the beginning of this post make complex things look simple. They make high-risk systems appear risk-free. They say, ah look at this funny thing here, it is called security and even you can do it. Go ahead!

I have actually been a Mick numerous times myself. I love doing things with my hands and consider myself a capable DIY’er – something of an orange or even green belt. And yet, dozens of times I have let YouTube DIY videos delude myself into thinking that a job is not as complex as I thought it was. Hey, just look how easy it was for that young couple to build a patio. Surely it can’t be that hard?

The outcome? I don’t want to talk about it.

And that’s why I stopped writing any manuals, guidance, todo’s, instructions, or whitepapers on security topics unless I am absolutely certain that the audience is capable of following them. Even when I do, I warn my readers that the job they are looking to embark on requires excellent technical competence, and I do so boldly and unambiguously. Security engineering is one of the largest surfaces for the dropped washers, and by directing irresponsibly you are playing your own part in creating the future chaos.

So, let’s re-iterate it for one last time:

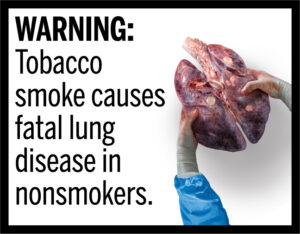

WARNING:

Security is complex and can be dangerous if approached irresponsibly. Please, do not make it look simple.

Picture credit: FDA