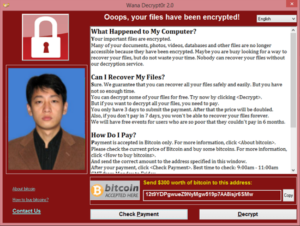

The second week of May appeared to be quite rich on cyber security news. On Friday, while the concerned public were still discussing clever techniques used by new French president’s IT team to deal with Russian government’s hackers, another major news has topped the bill – tens of thousands workstations, including those belonging to UK NHS trusts, have been taken down by a ransomware virus WannaCry. By Sunday, the virus had managed to affect over 200,000 workstations around the world, and could have affected much more if it wasn’t quasi-magically brought to a halt by an anonymous UK security researcher.

The attack summoned a lively discussion in the cyber security community and beyond on the reasons that led to the possibility of the attack and made it so devastating. A lot of fingers had pointed at Microsoft Windows, naming vulnerabilities in the OS the primary reason for the attack. The spiciest ones had even been calling to ban Windows in favour of other, ‘more secure’, operating systems.

Frankly speaking, it came to a bit of surprise for me. While there indeed had been a time when the Microsoft’s OS was an object for heavy criticism for its insecurity, the guys have eventually managed to do a really good job on catching up with the industrial best practices, and incorporated a decent set of security features into Windows XP SP2 and all versions ever since.

While there is little doubt that vulnerabilities in the corporation’s products were used by the malware to spread itself around, it is important not to confuse the reason for the attack – which is the cyber criminals creating the malware and launching the attack for easy gain – with the means they used to conduct it.

Consider chickenpox. This highly contagious virus spreads from one person to another through the air by coughing and sneezing. Still, no one of sound mind views human beings as the reason for the disease. Instead, the reason causing chickenpox is named as varicella zoster virus, while human beings are assigned with the virus carrier role. Getting back to the cyber space, virus carrier is the role played by Windows in the WannaCry case.

Modern software products are extremely sophisticated systems. We should admit that on current stage of human development it is nearly impossible to create a perfect, bug free software product. The chance of a compound system built up of a number of interconnected components having an exploitable security flaw is therefore very close to 100%. Virtually every software product can be used to perform a successful attack of one kind or another. The likeliness of a product to be used as a tool for a virus attack depends not as much on its origin, vendor, or technology used, but rather on its popularity and capability to spread the virus as quickly as possible. No doubt that if Windows suddenly disappeared with its market share taken over by OS X, the next virus we were going to see would have targeted the Apple’s platform.

And one more consideration.

Undoubtedly, the most efficient method of preventing infecting with chickenpox is to stop communicating with other people entirely. Surprisingly, no one uses that. People continue going out on Friday nights risking to catch chickenpox from someone in the bar. Parents continue taking their children to school, risking them getting the disease and spreading it to their siblings and the parents themselves.

Why? Because the common sense is not only about avoiding risk. In fact, avoidance is just one of [at least] four methods of dealing with risk, with reduction, retention, and transfer being another three. When mitigating the risk of getting chickenpox people normally stick to retention (“ah, whatever!”), or reduction (vaccination), but extremely rarely to avoidance.

The same approach can be transferred to the cyber space. There is no much need to make your computer a stronghold by protecting it from all possible attacks. You can spend a fortune and still never reach the 100% protection bar.

Instead, think wider, and try to mitigate the risk in a wiser way. It is very likely – see above – that one day or another you will get ransomware or some other kind of cyber scum on your PC. So instead of trying to avoid the unavoidable, why not think of the unfortunate event as if it is set to happen tomorrow, and employ the preventive countermeasures, such as data backup or emergency response plan, until it’s too late?

So who is to blame in the end?

The question becomes much simpler if we extend common crime handling practices to the cyber space. Information and computer systems are business assets. If a computer system becomes unavailable due to a ransomware attack, the attack obviously constitutes a criminal damage act at the very least. If unresponsiveness of the system leads to impossibility for the business to conduct its operations, the legal treatment for both the attacker and the victim would depend on the criticality of the business and its responsibilities as per the relevant acts of law.

Those will obviously differ for a corner shop and a hospital, with the latter being legally in charge of ensuring the continuity of its operations despite most of emergencies. Just as hospitals deal with potential power outages by installing emergency generators, they employ appropriate security measures to minimise the impact of cyber attacks on their operations – including their choice of secure operating system and any add-on protection methods. It is hospitals’ legal obligation to make sure they continue to operate at appropriate level if their system gets down due to accidental crash or deliberate attack. As for the attackers, they will most likely not get away with criminal damage in case of a large-scale hospital system crash, with escalated charges ranging from causing harm to health to manslaughter.

In this sense, cyber attacks are no different to traditional crimes against businesses and citizens. While their arena, methods, tools, and scale are very different to those of traditional crimes, the principal relationships between the subjects and objects of crime, as well as their legal treatment, largely remain the same.